Tuesday 20 October 2015

Strange to be crossing the Channel on my own, as far as I can recall for the first time since before we married, when passengers were crammed in rows of spray-lashed folding canvas chairs on the open decks of the Dover Ostende ferry and I was normally bound for Germany. Brittany Ferries are much more comfortable, the crossing calm and the ship almost empty. Jill was to have accompanied me to Paris for an international study day on book history at which I was invited to speak, but was detained in Exeter to look after her sister who had damaged her foot.

Wednesday 21 October 2015

A day in Caen with Geneviève to gather myself together for the Paris trip. My bag is heavier than expected and she has promised me one with wheels. A rainy day during which I helped her to take an old armchair and other items to the tip and we also embarked on an adventure to the mega-bricolage centre Leroy Merlin to buy two handrails for the stairs. It was hidden in the midst of a massive trading estate on the other side of Caen, reached eventually, after braving the racetrack which constituted the Caen ring road, through a maze of roundabouts and dual carriageways jammed solid with impatient motorists and van-drivers. It makes Marsh Barton and the other Exeter trading estates look like sleepy centres of rural industry. In the evening a friend visited and we were able to catch up on her disorganised lifestyle juggling a job in Orleans with the large school-house where she lived in the heart of the Normandy countryside and an old house in a state of perpetual renovation in Bayeux.

Thursday 22 October 2015

I was glad of the bag on wheels and for the lift to the station. In fact I had almost decided to give up on the visit and email my presentation at the study day as I had developed a feverish complaint overnight, my limbs aching and a lack of appetite. A couple of paracetamols deadened the symptoms and by the time I had reached Paris Saint Lazare at 12.15 I felt up to my original intention of attending the presentation of a thesis on printing history due to start at 14.00. So I dragged Geneviève's bag on wheels along the Boulevard Haussman, its grand stores looking a little dejected in the damp streets, to the Rue Richelieu, the site of the majestic old Bibliothèque nationale, now in the midst of a massive clean-up and reconstruction.

Just opposite was the École nationale des chartes, the prestigious centre for training archivists and documentalists. I was surprised to find it there as I remembered seeing the buildings of the École near the Sorbonne only last year and I learned later that it had opened its doors here only a week or so ago. The defence of the thesis was held in the main auditorium, the Salle Léopold Delisle. The defender was Andrea de Pasquale, recently appointed in Rome as the youngest ever director of a national library in Italy and his subject was "Jean-Baptiste Bodoni, imprimeur de l'Europe". I found him pacing up and down looking a little apprehensive and I was joined by half a dozen other members of the public. The international jury, when we stood for them to process in and take their seats, outnumbered the public and it was clear that, although they came from Brazil, Hungary, Spain and other parts of the world they all knew the defender. But if the outcome was cut and dried, he was not given an entirely smooth ride.

He gave a fascinating illustrated presentation on how in his previous post in the Ducal Library at Parma he had catalogued and digitised the wonderful collections of type punches, matrices, moulds, specimen books, correspondence and other items relating to this important printer and used the information thus gained to produce his thesis on Bodoni and his heritage. He was then questioned on the structure of the thesis, his use of references, the lack of emphasis on certain aspects of his subject. It was an interesting exercise as theses are not normally defended publicly in Britain – or at any rate I had never attended one. It began to drag on and I became concerned as I had an appointment at the Bibliothèque nationale (unfortunately in the modern François Mitterand book towers across the Seine, not the building just on the other side of the road) at 4.30. Fortunately the chairman of the jury must have needed the loo as he called for a break after two hours and I made good my escape, taking the metro to the dauntingly massive library complex on the south bank.

Once at the Bibliothèque nationale my first problem was finding the agreed entrance and my second was that Geneviève's wheely-bag was too big to be allowed in, so I had to telephone for Jean-Dominique from outside the building. I saw my contact pass along the massive entrance hall without seeing me, but managed to persuade the burly security guard to let me dash across to intercept him. All problems were resolved, my bags checked and I was led along endless corridors, through countless doors and up in a lift to an office which was a comforting jumble of old furniture, card cabinets and piles of paper, the walls lined with shelves of books and a gallery of family photographs and drawings. That was where Jean-Dominique worked in the section for retrospective cataloguing, drawing up an internationally used authority file of names of printers, publishers and booksellers for the period from the invention of printing to the 1830s, with a wealth of biographical detail. Who better than he to check for publication my biographical dictionary of 18th century book trade personnel for Lower Normandy, a continuation of the work of Alain Girard, Geneviève's husband who had died in 1995? We worked for over an hour comparing notes and discussing future progress – Jean-Dominique has a lot of other projects in hand at the moment – and our meeting finished agreeably with a beer in the pleasant library café.

I had survived the day but still did not feel 100% so took the metro to the little flat of Yves, Geneviève's brother, where I let myself in and found a welcoming bottle of wine. I did not feel up to tackling it on my own, but decided to explore the bustling rue Mouffetard to look for a bite to eat. The winding cobbled street, one of our favourite Paris places, a village in the metropolis, was lined with bistros and restaurants of all types but I did not have appetite for any of them, not even our usual Greek restaurant, so I bought some bread and spread which I consumed in the flat washed down with a tisane – rather a missed opportunity of an evening out in Paris.

Friday 23 October 2015

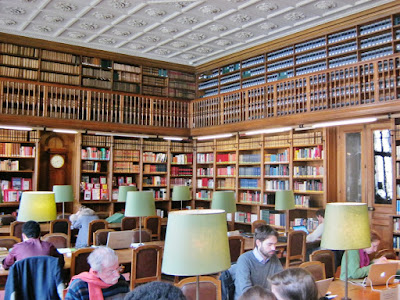

The international study day had arrived and I was up betimes, feeling I could survive the day if I was dosed up. By 8.30 I arrived at the Bibliothèque de L'Arsenal, a library I had not visited before. It must be the only library with an intimidating sculpture of canons at its entrance, explained by the fact that, before it was acquired by the marquis de Paulmy, a bibliophile whose collections formed the heart of the present library, it was indeed the Paris arsenal.

The portrait of the last director of the Arsenal looked down on our deliberations in the handsome meeting room. Andrea de Pasquale was there and I was able to greet him as il dottore. We remembered that we had previously met on the Black Sea in Mamaia at the conference organised by the notorious Florin Rotaru, the director of Bucharest Metropolitan Library, when he had asked for information on the Birmingham typefounder Baskerville. Much of the world of book history is a cosy little circle. Several of those in Mamaia were also in Paris at the defence of Dr Pasquale's thesis or the study day or both. Some of them were going off together on another jolly to Romania to a conference in Alba Julia (this one not organised by the disgraced Rotaru), visiting historic libraries en route. Meanwhile Jean-Dominique together with Christian Jensen from the British Library, who popped across from examining incunabula in the reading room next door, were off next week to Antwerp for a meeting of CERL, the Consortium of European Research Libraries, a body which among other activities maintains an important international name authority file.

The study day was entitled "Dictionaries and listings of book trade personnel in Europe and the world: experiences and prospects". It was organised by the University of Versailles who had got a mega-grant to fund a five year project to produce a printed and on-line directory of all publishers in France between 1789 and 1914 - one of those "long centuries" so beloved of historians. They wanted to gather ideas from projects that had been completed or were under way and also to hear from parts of the world where projects have yet to be put in hand. I was there to speak about my work on the London book trades, the Devon book trades and the "gens du livre" in 18th century Normandy. The sessions got under way more or less on time but, as is the way with French (and indeed many other) meetings of this kind it did not keep to schedule. Nevertheless they did find time for an excellent lunch for the presenters in a nearby restaurant, efficiently served, and a chance to chat about some of the issues raised during the morning. There was some interest in the format for data storage that I had devised as some projects had been having difficulties over choice of software. I have put a fuller account of the proceedings on my Exeter Working Papers in Book History blogsite together with the text of my presentation, so you are spared further detail, except to say that it was a stimulating and enjoyable day, and they did find time for the usual verre d'amité at the end - and to pack up any unconsumed nibbles for Jean-Dominique's children. The entire proceedings were videoed and I have been asked permission for my presentation – along with the others – to be put on the project website – a cult movie, I think!

Saturday 24 October 2015

I had noticed that the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal was open on Saturdays and, as I had not had the chance to look at it during the study day I decided to revisit it.

I had time to walk to the library through the Jardin des Plantes where the statue of the naturalist Buffon presides over the gardens in front of the Musée d'histoire naturelle.

The rain had cleared and it was a pleasant autumn day in the middle of the half term holidays. Parents were walking with their children on the way to the museum or the zoo, joggers were working out before work or study, and against the backdrop of the turning leaves there were still many flowers in the carefully aligned beds – as well as some gourds which put our own miserable display of pumpkins to shame.

Crossing the Seine and passing by the Bassin de l'Arsenal it became clear quite how much of the life of Paris takes place on or beside the water. Moored along the banks of the Seine are all manner of boats, some of them bateaux-mouches for sightseers, others floating restaurants, others places for living, some decorated with pots of flowers and even living roofs. The Bassin de l'Arsenal at the end of the Canal Saint-Martin was a crowded marina.

I wanted to take the opportunity of visiting the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal to check up on two of my Normandy book trade bods who had fallen foul of the authorities in 1771. The archives of the Bastille are held there and when I arrived I was relieved to be recognised by the curator who had welcomed us the day before. She registered me and, once I had deposited my bags, helped me to find the required boxes of papers in the computer catalogue.

It was a spine-tingling moment to hold in my hand letters written in such frightening circumstances by two of the individuals in my book trade directory. The prisoners bombarded the lieutenant general of police Sartine with letters begging for mercy. On 28 May the young bookseller from Caen, Manoury wrote: "I throw myself at your feet, Monseigneur, my eyes bathed in tears, protect a young man who is careless rather than guilty". On 5 June the Alençon printer Malassis le Jeune wrote "Monseigneur, I implore you to have pity on my fate, on that of my mother, my wife and my unhappy children". I was keenly aware that Manoury and Malassis were not just names in a dull dictionary of the dead, but men of flesh and blood. The real bad guy in the affair seems to have been Hovius, a bookseller in Saint Malo. It was he who had funded the printing of a forbidden work, assuring Malassis that it was authorised. He had then passed the bulk of the edition to Manoury for distribution, again keeping quiet about its real nature. A declaration by Malassis states: "Hovius abused his youth and inexperience when he commissioned him to print the said work". This seems to have been accepted as Malassis was released on 14 July while Manoury and Hovius had to wait for an order from the King dated 30 September 1771.

Having accompanied my prisoners safely out of the Bastille, I left the Arsenal and crossed the Seine to the Quartier Latin to keep another appointment at the Collège des Bernardins. I was due to meet my German friend Hubert there for lunch. Actually I knew that just before my departure he had cancelled his tickets because of ill-health, but at the appointed hour I was there with an empty seat opposite and had my quiche and salad in the peaceful calm of the gothic hall. The gentle figure of Christ, found during excavations when the hall was restored, looked down on the table. Friends of Hubert said that the face of the statue bore a striking resemblance to his, so in a way he was present after all. Hopefully he will find his way there in good health next Spring. The Bernardins is one of his favourite locations in Paris.

I set out along the Boulevard Saint-German, past the tables of diners enjoying their lunches in the bright autumn sunshine beneath the trees that lined the avenue. I was half looking for an exhibition on the history of writing that I vaguely remembered passing on a previous visit so I also wandered along the rue Saint-André-des-Arts with its many art galleries. In front of the church of Saint Germain-des-Prés an excellent traditional jazz group were playing and I stayed to listen for a while. Eventually the Boulevard Saint-German came to an end in front of the Assemblée nationale and I decided to give up on my exhibition and to cross the Seine to visit the Petit Palais.

To my delight I discovered a special double exhibition of prints under the title "Fantastique" covering Japanese and French prints of the 19th century with a theme of fantasy. A short queue of twenty minutes or so and I was inside. Japan was represented by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) a leading master of Japanese ukiyo-e coloured woodblock prints of which several hundred were on display, mainly from a private collection. He is best known for his depictions of the battles of legendary samurai heroes, the inspiration for a host of tattoo artists and authors of manga comics.

I found these too violent and confusingly over-active but fortunately there was much to enjoy in his very wide range of work including his portraits of beautiful women and Kabuki actors. These last were prohibited when the regime sought to suppress immorality in the 1830s but Kuniyoshi found ways round this, disguising the actors as cats or other animals, though still recognisable as individuals, or imitating the graffiti on the walls of warehouses.

There were atmospheric landscapes, scenes of everyday life, caricatures, puzzle pictures, all of them carefully carved as coloured woodblocks. He was influenced by Western techniques, in one print basing his depiction of elephants (which he had never seen) on 17th century Dutch engravings.

The European section was based on 170 items in the collections of the Bibliothèque nationale and traced the theme of fantasy that ran like a black thread through the 19th century. Some earlier emblematic prints were shown, Dürer's Melancholy, Rembrandt's Dr Faustus, Piranesi's prisons, but it was above all the Caprices of Goya that set the atmosphere, aided too by the development of lithography as a more direct medium of expression than engraving on metal or wood.

The general impression was one of menace - the figure of Mephistopheles flew across the scene, the contagious spirits of cholera writhed in the clouds above Paris, in a more humorous vein Lucifer played Tartini's "Devil's trill" sonata while the composer dreamed. A wide range of artists were represented – Delacroix, Gustave Doré, famous for his illustrations of The rime of the ancient mariner, right up to the symbolist artist Redon. The exhibition was crowded and there seemed to be no objection to photographs being taken, so I joined in, with mixed success.

Back outside Paris was alive with contemporary arts, part of the Champs Elysées being lined with tented galleries, a massive exhibition in the Grand Palais and statuary everywhere. Even outside the Petit Palais there was an example which caught my attention because it was promoted by Hauser and Wirth whose gallery in Bruton in Somerset we had recently seen. They also had more prestigious galleries in Zurich, London, New York and Los Angeles. The present offering, a tumbled wall of breeze blocks hastily assembled with yellow mastic, presumably intended to imitate marzipan, led me to wonder whether it had been deliberately kicked over by the artist or assembled complete with an invitation to the public to indulge in a session of interactivity to demolish the structure – this is unlikely as notices told us not to touch the works of art - or indeed whether vandals had attacked it during the night.

Further on in the Tuileries were other questions: what was the statue that looked rather like a giant toffee apple meant to represent? I was not alone in wondering and saw people from the swarms of strollers (sorry, I mean crowds, we mustn't depersonalise people who migrate to Paris) walk away from the notice shaking their heads in incomprehension. By the Place de la Concorde there was a group of large interactive sculptures, one like a complex multicoloured revolving door where it was possible to see the spectators wandering around inside trying to find their way out. There was a long queue for another – a sort of squashed accordion with the ribs picked out in neon lights.

But the best show was provided by the last rays of the sun lighting up the trees in the Tuileries at seven in the evening, the last evening before the clocks were put back.

I took the metro back to the rue Mouffetard and realised that for the first time in several days I actually felt hungry. I managed to get a table in the packed Greek restaurant and was placed next to the musicians – I did not realise that they had live music in the evenings. A diner at the next table told me that this was the only restaurant in the rue Mouffetard which was full, and that was because it was so good – and as someone who lived locally he should know. And it was a pleasant experience, the food excellent value, if a little formulaic, the staff happy in their work, shaking regular customers by the hand, and joining in with the music from the bouzouki and guitar duo, which was not overpowering, and a buzz of conversation and enjoyment from the diners.

Sunday 25 October 2015

My last full day in Paris, and I had an invitation from Geneviève's daughter Cécile to visit for coffee in the afternoon to see their new flat and new baby. I started with a very strong morning coffee at a brass topped table in the exotic Centre Islamique, in the same complex as the main mosque, and continued across to the Ile Saint Louis, closed to traffic this Sunday, with a wonderful early morning view of Notre-Dame and the Ile de la Cité, into the old area of the Marais where I discovered the medieval Hotel de Sens and the Renaissance Hotel de Sully which was not spared a modern art installation in its carefully tended gardens.

I planned to visit the basilica of Saint Denis in a suburb to the north of Paris not far from Saint-Ouen where Cécile lives. When I emerged from the metro I found myself in a different world. Once escaping from the brutalist and shabby shopping centre I found a market in full swing in the main square and white faces were definitely in the minority. The market square led to the parvis in front of the basilica where young men were break dancing. The basilica itself was gleaming white after a recent restoration, the clock on its gothic façade picked out in gold.

In medieval times it was one of the most important abbeys in France and it was here that most of the kings and queens of France had been buried from the times of good King Dagobert until the early 19th century. The existing tombs and monuments date only from 1263 when St Louis commissioned the first sixteen recumbent effigies to reinforce his dynastic links with his Merovingian and Carolingian predecessors. Now some monuments of 42 kings, 32 queens and 63 assorted princes and princesses are aligned around the choir of the abbey church and in the crypt where excavations have also laid bare some of the original medieval sarcophagi.

The revolutionaries broke open the tombs around 1790 and scattered the remains of kings and queens promiscuously in a pit in the grounds of the Abbey. At the restoration they were gathered together reverently and placed in an ossuary in the crypt.

The ubiquitous Eugène Viollet-le-Duc was involved in a programme of restoration and the first Bourbon monarchs were also commemorated there, as was Louis XVII, the uncrowned king who died aged ten in 1795 and whose withered heart can be seen as a latter-day relic beneath his medallion portrait. The whole collection provides an interesting account of the changing styles of funerary monument across the centuries and colour was added to the display by a series of specially commissioned ceremonial robes in the side chapels of the crypt.

Apart from the abbey there is not much to detain the visitor to Saint-Denis (unless one is a football fan visiting the Stade de France) although I did discover an interesting monument to slavery, only abolished in the French colonies in 1848. The delicately curved metal frame supports 213 labels, each with the name and number of the last slaves to be liberated in Martinique and Guadeloupe.

I left a little time to explore Saint Ouen as it must be one of the largest building sites in France. An industrial area by the former docks on the Seine had been cleared, except for an incinerator and a massive district heating plant, both of which belched fumes, and was in the process of being filled with residential flats. For several years there will be great disruption - local shops have yet to arrive, pavements have still to be laid, rubbish skips are filled with rubble and with packaging from people moving in to the flats.

But the architecture is varied, there is some social housing, and in the middle is the Grand Parc which includes some allotment gardens, slotted incongruously into the development. Cecile and Jean-François share a small plot with a dozen other members of a residents' society. I imagined the committee meetings of the society: who would dig where, who would sow what, who would tend which sections, who would be entitled to pick which crops and when - and so on.

Later I was able to see one of the flats from inside – a pleasant newly completed apartment on two floors and, because they were on the top floors, two balconies with a view over the park. Baby Lisa made her presence felt and coffee was extended into supper and conversations on a range of topics: the problems of settling into a new apartment in an area like Saint-Ouen, social problems, politics, migration, even libraries as Cécile has followed her father Alain into the profession. An enjoyable end to my stay in Paris with an easy return journey by metro to my little pied à terre on the other side of the city of Paris.

Monday 26 October 2015

Not much more to report really. An uneventful return to Caen by train was followed by a day in Caen when Geneviève invited three library friends to share a poule au pot for lunch – a lunch which started about 12.30 and finished about 4.30. Much chat on many topics including the massive new library which is under construction in Caen. France is not immune from cuts. A change of regime in the municipality had led to the new politicians deciding to cut the number of posts envisaged to service the new building. This had led to strong objections from the director of the library and, as they were unable to dismiss her from post, an advertisement had appeared for an assistant director who would be given many of the responsibilities for implementing the new service. A lot of things to ponder on the ferry during a calm, quiet crossing to Portsmouth on Wednesday, then by train to Salisbury which managed to miss the connection to Exeter – welcome back to England.