Friday 28th June 2013, Exeter

At this point our travel report ended abruptly. It is now nearly two months later and my memories have faded. We are now back in Exeter and once again I have been attacked by the shingles virus in my eye. It has left me debilitated and weary. Very slowly I am beginning to regain my health though I spend far more time than I would wish looking “interesting and delicate” on the sofa. I have been unable to read or use my computer because of the pain resulting from the damage to my optic nerve. I have been warned it could take a very long time to recover and meanwhile see the world dimly, through a haze. This would seem to have been caused in part by an allergic reaction to

the anti-viral cream used in the eye. I am though showing signs of recovery and my vision has started very slowly to improve. Fortunately the other eye is unaffected, the main problem being getting the two eyes to focus together.

We left you in our Jura village of Champagne-sur-Loue. (Lucky you). I will now endeavor to summarise what I can remember from the rest of our journey until we returned home in late May.

We spent a week with our friends and most of it was wet. We took favourite walks through the woodland, followed by the cattle that roam free on the Clos above the village and were curious to see weird two-legged creatures amongst the dripping trees, wonderful spring buds and blue pervanche flowers. We on the other hand, were more than a little nervous to encounter these frisky creatures deep in the woods where they hustled each other on the narrow track to get closer to us.

It was with relief we crossed the cattle grid and entered the open hillside were the vines of the villagers are spread out in their serried rows, the leafbuds just beginning to open. Roland has spent many hours recently up here tying his vines, weeding them and spraying them with sulphur. It is all a great deal of work for him when he is in his 80s now. Hugues comes every weekend to help his parents and Susanne is often with Roland for company. Despite his mobile phone Susanne is always anxious when he is up here alone.

From here we could see the blue shape of Mont Poupet where Louis Pasteur carried out experiments that helped save Europe’s wine trade from the dreaded Phylloxera that almost completely whipped out the vines of France and the rest of Europe during the 19th century.

One day we drove up to the source of the Lison and the cascades du Herrison returning along the quiet mountain roads flanked by dark green conifers, perhaps one of the chief exports of the area. On the wet and dripping hillsides the healthy Jura cattle munched relentlessly on to produce the milk for the inestimable Comté cheese – the only cheese Ian has even been known to really enjoy.

On the day before we were due to depart the sun finally put in an appearance. We made the most of the opportunity by visiting a huge vide grenier (car-boot sale) on the banks of the Loue at Quingey. It was a complete quagmire with all the residents from many miles around converging in the hope of finding a replacement statue of St. Francis for the dining room, a massive crucifix for the yard, a rusty cauldron or possibly an unopened jar of udder cream for the cows! The possibilities were endless and all seemed satisfied! We nearly bought a Peugeot coffee grinder for Kate’s period kitchen but decided it was too expensive. (Fortunate as Geneviève had meanwhile found one at a vide grenier in Caen that was in better condition and cheaper.)

Back in the little town we treated ourselves to coffee in the sunshine near the church and watched as everyone poured out and headed straight down to the river where beer and hot dogs were selling to eager customers. Eventually even the priest and his curate emerged still in their robes, locked the doors and headed off to join in the excitement and enjoy a hot dog with their parishioners. We saw them later, the curate clutching a battered but saintly statuette under his arm and wearing a very satisfied smile.

Returning towards Champagne we diverted along a road we’ve never before explored. Along a track through the woods we saw a sign directing us to a monument to aviators who died here in WW2. Eventually we found it. They had been dropping supplies to Resistance fighters and had come in too low, crashing into the trees. All were killed.

We remembered some Commonwealth war graves we had seen in the cemetery at Arc-et Senans and had wondered about. Another piece of the jigsaw of the wartime history of this region, so near to Germany and on the border between Free and Occupied France, now slotted into place. On our way home we stopped off to see once more the graves of the airmen. No explanation linked the two places but the five British and three Australian aviators in the cemetery were no longer simply names from the past. They had lost their lives trying to help their brave French allies and we had just come from the exact spot of their brave but tragic end. On one grave there was a plaque to the widow of one of the young British airmen. Her ashes had recently been placed there, reuniting her with her husband at last, after some sixty years!

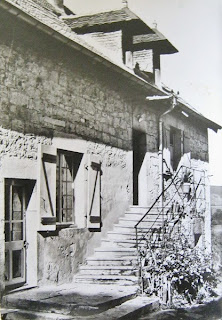

Of course we spent much time reminiscing upstairs with Susanne in her big kitchen overlooking the former convent and school. The mayor of Champagne wants to encourage the village to link back to its former history and is hoping to hold a reunion of former pupils at the convent school if he can track some of them down. Once my eye is well enough I need to go through my letters and photos as I probably hold more material and clearer memories than any of the pupils or former teachers at the school. It was, after all, half a century ago but I still remember the names of some of the pupils and know the whereabouts of some of the sisters! Those still living are scattered in Dominican

convents across France. The thought though of writing it all up in French for the mayor is rather daunting me and I use my eye as an excuse to delay.

We left Champagne in the rain. I hate leaving, especially as our friends get steadily older and their way of life continues to make its heavy demands. What they could do easily in their twenties and thirties is more difficult and takes longer in their seventies and eighties. They remain cheerful though and waved us off with calls to return soon. We certainly will, for as long as they continue to live in the village.

Our intention was to camp a couple of nights near Dijon and re-explore the city. The rain was falling again as we set off and the radio warned of red alert for flooding in the Cote d’Or. If it was wet in the Jura, the area as we approached Dijon was far worse. Rivers had burst their banks, canal-side lockkeepers’ cottages were cut-off and surrounded by water. Cattle stood huddled together in the mud in the top corner of their fields whilst the unlucky ones on lower pastures moaned plaintively, up to their hocks in water, their breakfast under a foot or two of water!

We stopped off at the mediaeval Abbé de Cîteux seen across flooded meadows, for lunch in Modestine. The abbey surroundings were underwater so we could not explore much. The abbey, which was the

origin of the Cistercian order, today houses brethren of the strict observance, better known as Trappists (our auto-correct suggests Rapists!). It appropriately offers visitors a “chemin du silence” illustrated at intervals with mosaics on the pavement illustrating each century of the abbey’s history. We were unable to follow it all as it was flooded but saw a mosaic commemorating the famous scriptorium and library. There was also an exhibition commemorating the 800th anniversary of the arrival at the abbey of Bernard of Clairvaux who, together with his companions, founded the monastic order there. There was an interruption in the history of the abbey after the Revolution, the library at one stage being converted into a theatre, but the site was repurchased in 1898 and, a bit like Buckfast Abbey in Devon, the monastic life was revived. The abbey church is therefore not medieval. It is less attractive than that at Buckfast, having only been completed in 1998. We also found a shop with the normal mix of religious literature and trinkets, herbs, honey, candles and above all the cheese for which the abbey is famous.

By the time we reached Dijon it was late afternoon and we decided to head straight for the campsite and explore the city the following day. It took a while to cross Dijon with its tram tracks and multilane ring-road but eventually we found the camping ground. It was under several feet of water with a fast flowing river gushing through the facilities. The area was cordoned off and the firemen of Dijon were fruitlessly attempting to pump the water back into the already swollen and flooding river. There was no way we could camp and we had no option but to drive on while Ian thumbed our directory for another site. None were to be had within forty kilometres of Dijon and we were obliged to miss the planned visit to the city and drive on, hoping the next site would be on higher ground. It was indeed, set in woodland with open vistas. We spent a very pleasant evening. The sun came out and we lingered outside with a glass of wine long into the evening.

Next day was 5th May. As we drove on through the green pastures the clean white walls of a tall gothic church rose above the rooftops of an approaching village, rather like an ocean liner. We simply had to stop to investigate and parked in an empty square in front of the priory church of St Thibault-en-Auxois. The height of the lofty choir made it seem to be a church started with great ambition but never completed. The door was locked, so we contented ourselves with admiring the elaborately decorated 13th century portal with the finely carved medieval door and set off to explore the attractive village.

On several of the village houses we noticed fragments of carved masonry built into the walls of the old farm buildings. The village also had a handsome lavoir and we were intrigued by a proud and colourful display of badges won at agricultural shows over many years by a local farmer for his herd of Charolais cattle.

On returning to Modestine we found the door to the priory church was now open. We entered to be dazzled by the slender soaring gothic tracery of the apse, in front of which was a magnificent polychrome 14th century reredos. On it were carved scenes from the life of St Thibault. Inside the priory we found the president of the Friends of Saint-Thibault-en-Auxois, a well-informed and enthusiastic man, who had opened up the church to await the arrival of a conservator who was due to look at the old harmonium. While waiting he showed us around the priory, explaining the images on the reredos and something of the chequered history of the building.

woods in Salanigo near Vicenza where Gautier died. During their travels Thibault seems to have been tempted by a devil, according to the scene on the left. The death of Thibault at Salanigo is shown on the right. He had been joined in his retreat by his mother shortly before his death.

The church was started in about 1260 to receive the relics of St Thibault. It was thought that the architect responsible for the Sainte Chapelle in Paris had a hand in it, and its lightness and loftiness were certainly comparable. The architects had used iron rods to tie together the slender columns. We also learned that the church had in fact been completed but the nave had collapsed after being struck by lightning in 1686. Our suspicions about some of the statuary on the portal were confirmed when we were told that the ubiquitous Viollet-le-Duc had given it a make-over in the 1840s.

The conservator arrived and we left the church to the strains of Handel on the harmonium and set out to find the location of the castle once owned by the Seigneur de Thil whose tomb we had seen in the church. The Butte de Thil is a conspicuous hill a few kilometres distant where we parked for lunch seated on a bench overlooking the surrounding countryside while bees gathered nectar from the surrounding buttercups and cowslips. Further off were several bright patches of yellow where fields of oilseed rape ripened for cattle fodder.

My navigator, Ian, then directed me down lanes in the deep countryside to reach the little village of St Leger Vauban, so named as the birthplace of the military architect of Louis XIV whose forts and defences are found in every corner of France. Indeed, after the Sun King himself he is probably one of the most well known Frenchman of that era. By contrast his home is no more than a humble village cottage, now housing a museum while Vauban stands resplendent on a column in the centre of the village green. It is a pleasant village but considering Vauban’s importance to the king there is little to mark his passing.

Not far away we came across the curious village of Quarré-les-Tombes. Curious because excavations in the churchyard discovered over one hundred empty Merovingian coffins hewn from solid limestone and dating from the 6th or 7th century. None would seem to have been used so why and how do they come to be there? They now lie side by side all around the 16th century church, many broken or cracked. There is something disquieting about them. One theory is that the village made coffins speculatively and this was a 6th century storage depôt! Another theory is that the acidity of the soil destroyed the bodies whilst the coffins remained intact. Both seem unlikely explanations. The stone has been proven to come from a long distance away and it is unlikely it would have been transported to this particular village for shaping rather than having been worked at the quarry.

Next we continued to the delightful mediaeval town of Avallon in the heart of the Burgundy region some 50 kilometres south of Auxerre. The picturesque cobbled streets of the old town, constructed on a promontory overlooking the river Cousin, are lined with white stone or timber-framed mediaeval houses.

During the afternoon we passed through the village of La Chapelle-Angillon. Here we found ourselves on the bank of a wide lake with a château on the further shore. A signboard at the entrance to the village linked it with the writer Alain Fournier. The overcast drizzly weather evoked memories of reading many years ago Le Grand Meaulnes, with its dream-like evocations of the parties in the grounds of the lost domaine, deep in this part of the French countryside. So we stopped to soak up the atmosphere. The château was closed and has nothing to do with the “lost domain” – the title of the English translation. Although the village is the birthplace of Alain Fournier, where his father taught in the village school, we never actually discovered the house where he was born. The museum building in the grounds of the château seemed rather forlorn and neglected, and we gather from the web that there is dispute with the Maison-École du Grand Meaulnes at Epineuil-le-Fleuriel who claim that it is merely made up of a few panels from an exhibition dating from the 1980s and the association are taking legal action for abuse of the designation Musée Alain Fournier!