Tuesday 17th April 2012, Antwerp, Belgium

If you approach the Plantin-Moretus Museum through the Sint Anna foot tunnel under the Scheldt River,as we did, you emerge in a surreal manner right into the middle of the town – rather like stepping out of the back of the wardrobe into the world of Narnia. The Plantin-Moretus Museum is just round the corner, its baroque main entrance facing onto the quiet square of the Friday Market and its original Renaissance façade lost in the shadows of a narrow side street.

It really is a remarkable institution, rightly inscribed in the two UNESCO registers of World Heritage Sites and Memory of the World. Christopher Plantin (c.1520-1589) was one of the major scholar printers of 16th century Europe and the Moretus family continued the tradition, making the building a major cultural centre of Antwerp into the 18th century. Not only that, but he was one of the first printers to produce works on an industrial scale. In 1876 the last of the Moretus family passed the building and its entire contents to the city of Antwerp. The result is the survival of an important printing office, with all its equipment and archives, and the living quarters of one of the most important families of this major city together with the furnishings, works of art and the scholarly library of more than 30,000 volumes.

When we arrived, the curator greeted us and rushed us off to see the special exhibition “Mercator: exploring new horizons”, commemorating the 500th anniversary of the birth of the cartographer Gerhard Mercator (1512-1594). She was especially enthusiastic about being able to display a portolan chart of Asia borrowed from the Municipal Library in Valenciennes, beautifully illuminated, certainly not the sort of thing that a sailor would keep in his pocket.

There were other wonderful things on display as well:

There were also early travel and navigational works – most of them from the remarkable collections of the Plantin-Moretus library. Later in the main displays we saw archives with entries relating to Mercator.

The permanent exhibition was as wonderful as when we first saw it many years ago. Of the printing departments the most stunning room is the workshop with its row of eight wooden presses, two of them dating from about 1600 and the oldest known surviving examples anywhere.

There is also the other paraphernalia of a printing office:

The type foundry, with the stoves set up in the 1620s, is on the first floor.

This too has its associated artefacts, punches, with individual letters painstakingly carved on the end of a steel rod, matrices, produced on a flat bar of copper by striking it with the punch, typecasters moulds, into which the matrices were fitted and individual pieces of cast type.

There were also racks of cast type – in 1589 Plantin had 22 tonnes of cast type and there are still ten tonnes in the Museum today. The individual letters were assembled into lines on composing sticks and transferred to galleys, and there are examples of these with impressions taken from them, as well as woodcut illustrations, frames, initial letters and ornaments and copperplates, many of them engraved for the Moretus family after designs by Rubens.

There are also the rooms where the correctors worked, the office and strong room and the shop, still with unbound works on its shelves awaiting customers.

The business had its ups and downs, particularly for the founder Christopher Plantin, who had to steer an uneasy course through the religious wars that ravaged the Spanish Netherlands in the 16th century. At one stage in the 1580s he was forced to leave briefly for Leiden where he became university printer, a post that was continued by one of his son-in-laws Franciscus Raphelengius (1539-1597) who converted to Calvinism. However in 1570 he was granted the post of “architypographus” for the Spanish Netherlands by Philip II with the exclusive right to produce and sell service books and liturgies. His business expanded and five presses in 1568, he was running sixteen by 1575 and with seventy employees it was the largest printing office in Europe. On his death the business was taken over by another son-in-law Jan Moretus (1543-1610) and continued under the management of a dozen successive members of the family until the late 19th century. The early successors continued Plantin’s tradition of scholarly printing, but after about 1650 the main publications were liturgical works for the Catholic Church, both in the Low Countries and Spain.

After initial problems the family did very well from the privilege of liturgical and official printing and this is reflected in the living quarters, which are those of a wealthy patrician family, the rooms lined with embossed leather coverings and filled with furniture, paintings and other works of art, many by Rubens and other noted painters.

The printing offices and living quarters were built over a period of time around a beautiful central courtyard.

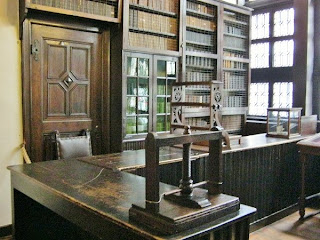

The most impressive rooms in the living quarters are the two library rooms, the larger of which also served as a chapel which explains the presence of a painting of Christ on the cross by Peter Thijs.

Plantin started the library as a reference collection, including texts which might served as a basis for scholarly editions and works such as dictionaries and accounts of travel and atlases. The collection was developed by the Moretus family until it contained more than 30,000 items. They are displayed in rooms throughout the house and provide an outline of fine book production throughout Europe. Of course many of Plantin’s own productions are on display including his wonderful polyglot Bible.

Plantin produced 2,450 works over a period of 34 years and over 90 per cent of these are represented in the collections. There are also many works by other Antwerp printers. The city was the major centre of printing in the southern Netherlands and there are incunabula by Mathias van der Goes, Geraert Leeu and others. There are also more than 500 manuscripts, the earliest dating from the ninth century and including beautiful books of hours. The earliest printed book in the collections is a copy of the 36 line Bible, printed with Gutenberg’s type, probably in Bamberg by Albrecht Pfister about 1460.

Early French printing is represented by the Estiennes, including their scholarly dictionaries

Italy by the careful editions of classical texts produced by Aldus Manutius, Spain by the Complutensian polyglot Bible, produced in Alcala de Henares by Brocar between 1514 and 1517 – a precursor to Plantin’s own polyglot Bible.

There are many maps and atlases, including a wonderfully detailed bird’s eye view plan of Antwerp by Virgilius Boniensis, dating from 1565.

There are also several panoramas, mainly of triumphal processions.

The graphic collection includes sketches by Rubens and others for illustrations, title pages and ornaments, including Plantin’s own printer’s device of the golden compasses with the appropriate motto “Labore et constantia”.

This constant work is revealed not only in his motto but in the massive archive which includes his dealings with many of the leading thinkers and artists of the day. Scholarship and culture breathe from the walls of this building. There is a room where the philosopher Justus Lipsius was lodged at Plantin’s own expense. Plantin was also a writer and poet. He participated in the production of early dictionaries and members of his family were also men of learning – Raphelengien became professor of oriental languages at Leiden University and cut a set of Arabic types.

We ended up spending most of the day in the museum, and we could easily have gone back for more the next day. We made up for this by acquiring an excellent guidebook by the curator Dr Francine de Nave and the Plantin specialist Leon Voet, which reproduces many of the star items in this unique collection.